Since late 2017, I have been pursuing a practice research PhD at RMIT University in the School of Media and Communications. Sounds cool, but what exactly does practice research mean?

“Practice as research might denote a research process that leads to an arts-related output, an arts project as one element of a research process drawing on a range of methods, or a research process entirely framed as artistic practice.”

University of Manchester)

Practice-related research goes by many names, ‘such as “arts-based research”, “practice-based research”, “practice-led research”, “practice-centered research”, [and] “studio-based research”. These are more or less used synonymously’ (Niedderer and Roworth-Stokes, 7). The term ‘practice-led research’ is typically the one used most consistently, perhaps because it puts the creative practice ahead of the research, a horse before a cart, as it were (Skains, 2018). The research question, which shifts and never quite settles unlike the traditional PhD, should also articulate how the practice is the research.

In my case, my PhD involves elements of creative practice produced prior to as well as during the PhD. My practice research journey began with my ekphrastic work. I thought that elucidating a ‘conversation’ between text and image was a way to define my practice. This led to an expansion of scope into collaborative practice, which segued into spoken word and various dimensions of performance.

One of the ‘problems’ that I faced in articulating my practice is that I have trucked all over the landscape. Publishing, performing, exhibiting and working with a range of artists from various disciplines on projects that are equally varied in theme and style does not easily lend itself to a focused ‘slice’ through the practice, which is what my supervisors at RMIT would like to see. Currently, my dissertation has moved into something extremely personal; my faith. Spurred on by a memoir-in-progress of twelve years in Christian fundamentalist churches in Singapore, I am writing, researching and producing work that negotiates my loss of faith from the perspective of a creative practitioner.

This, seems to be rather distanced from the subject matter of the journal, which located me in a very different space. Initially, I began approaching the residency like an extended travel trip. I thought that I would probably come away with a bunch of ‘travel poems’ and photographs that would accompany them. But what I created couldn’t have been further from that. ‘Far From The Plastic World’ was birthed from an impulse to explore subject matter without an endpoint in mind. It was also birthed out of frustration. I could not photograph freely, bound as I was by Guna laws and social mores that felt archaic and unreal. Yet, I had to honour and respect those practices if I wanted to remain part of the life of the village.

In putting the journal and its related media together, I started reading about autoethnography, which seemed to be a useful methodology for approaching this project. One of the many definitions of autoethnography is about “reflexively writing the self into and through the ethnographic text, isolating that space where memory, history, performance, and meaning intersect” (Denzin, 22). However, assuming the role of a creative autoethnographer was not what I had in mind when I was accepted for the residency. Autoethnography emerged in retrospect as a way of documenting, reflecting on and providing a frame for my experience.

The journal became an intersecting space that held both art and an informal cultural anthropology. Art is evinced through poetry and photographs. The latter are sometimes documentary in nature, but also have a representational element to them. The video and audio clips are definitely a lot more documentary-like in nature. The journal itself is a hybrid text.

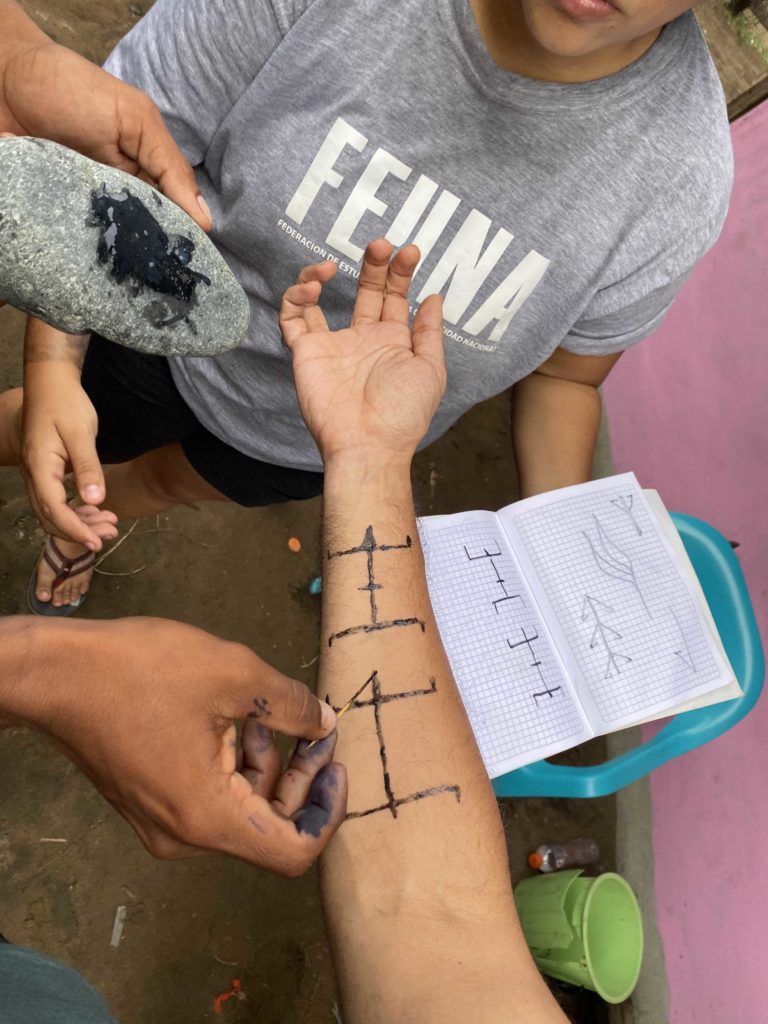

While the journal’s form is clear, its contents aren’t as obvious. Certainly, it is a document that aims at communication. But it also holds fragments of observations from the other artists and myself. These sit within the landscape of the residency that extends far beyond the walls of the residency house. As Rutten says, “Autoethnography is both process and product” (Rutten, 300). As process, autoethnography researchers study a culture’s practices, values and beliefs then “retrospectively and selectively write about epiphanies that stem from, or are made possible by, being part of a culture and/or by possessing a particular cultural identity” (Ellis et al. 2010, 8). And much like how I brought my own practice in poetry and multimedia to Armila, other artists came with diverse backgrounds in sculpting, drawing and performance art. All of us wrestled with translating and transforming experience into forms that we were familiar with.

However, I believe that the journal became the nexus of my autoethnographic impulse. The form of the journal was a mix of observations of activities that we engaged in as artists, descriptions of the village life and snippets of ‘lectures’ by our host, Nacho. The journal thus becomes a repository of how I engaged in a more expansive way with the rich landscape that I found myself in.

The access to experience and the permission that was given to learn, listen and document was only possible because of the La Wayaka residency that was already in place and the relationships that the founders of the residency had established with the Guna in Armila. The anthropological angle is an unforeseen byproduct, a wonderfully rich outcome of working within such a vibrant and rich environment. The tapestry of Guna history, spirituality, daily life and culture is fertile earth for creative seeds to bloom.

So what is the point or value of building this repository? The journal reflects what Anderson defines as embodied writing, “relaying human experience from the inside out and entwining in words our senses with the sense of the world” (Anderson, 84). As a creative process, it gives rise to creative research insights into the Guna people through my personal experience, leading to further possible areas of research by offering a perspective that sits between the fleeting tourist gaze and the embedded eye of the writer as ethnographer.

References

Anderson, R. (2001). Embodied writing and reflections on embodiment. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 33 (2), 83-98.

Denzin, Norman K. (2013). “Interpretive Autoethnography” in Handbook of Autoethnography, eds. Stacy Holman Jones, Tony E. Adams and Carolyn Ellis. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Ellis, C. Adam, T., Bochner, A. “Autoethnography: An Overview Forum: Qualitative Social Resarch, 12(1). (Online, last accessed 22 July 2020)

Niedderer, K., and Roworth-Stokes, S. 2007. ‘‘The Role and Use of Creative Practice in Research and Its Contribution to Knowledge.” In IASDR07: International Association of Societies of Design Research. Hong Kong.

Rutten, K. (2016). “Art, ethnography and practice-led research”, Critical Arts, 30:3, 295-306.

Skains, R. Lyle. (2018). “Creative Practice as Research: Discourse on Methodology”. Media Practice and Education, 19:1, p. 82-97.