An occasional series that reflects on everyday images. Part of the word ‘ordinary’ comes from arə, a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “to fit together.”

These are kneeling pillars, holding up the shelter of their souls, keening with proffered incense, oblivious to the residents strolling home behind them. Nobody stops to gawk. It is a private moment in an intensely public space. But it is also quite an odd place for prayer.

Perhaps a temple was once here. But at first glance, the women’s gaze is fixed on nothing more than the detritus of a city: a storm drain, an overgrown grass verge and beyond, the faceless car park obliterating whatever was once in the name of convenience. Their posture of prayer recalls only an an echo of older stories.

Perhaps the women pray as a way to return a temple to life, to call a wandering god back; for favour and faith, to allay a sense of the falling dark.

Someone with an inherent sense of shape, colour and order has created a still life for a mise-en-scène of casual labour.

A ladder leads the eye up the plain tiled wall and then we head left to the pail and watering cans, their primary colours leaping out along with their varied shapes. Above are window panes, styled similarly to the tiles, providing an unironic reflection, one that is tinted a dirty green. Whether that is from the vagaries of weather or some ersatz design element is unclear. The wall as canvas is suitably splashed with the impertinence of dirt, that inevitability of living in a perpetually dusty environment. But here, it adds grit and gravitas.

The way we climb into the scene is through the ladder, that most quotidian of work tools. Everyone needs a ladder; to extend themselves beyond their reach, to look a little above, yet not quite reaching the clouds, to feel what it’s like to climb. Ladders are palatable trees, bereft of branches, far easier to scale. And yet, standing on the top of a ladder, with no handholds, still gives us a thrill.

It isn’t dumping if it can be reconstituted.

But can you recycle what is still raw?

The trunk, sliced haphazardly like a log cake, is still unchanged, open to suggestion. It occupies a yellow box of punitive possibility, a recalcitrant before a bevy of brethren long since consigned to the shape of their lives.

A lone human stands atop a container, holding a frame of some kind.

Wood seems destined to become a way in which we hold our selves before the world, sliced into ever thinner pieces until it bends with a breeze or cracks from the impossibility of its skinny logic.

And this is is what gives the incredulity to these pieces of wood. Did a tree offend? Was this a furniture project abandoned? Or is this the beginning of an upcycling penance?

We are all these shapes and sizes.

We are the visible and invisible gazes. We look into spotlight and sunlight, across a sea printed like a dream. We are the invisible current, splotches of colour, carefully coiffured tresses.

The dressed and the undressed. Each pose a fever of suppositions and expectations. We are knotted and pressed against the day.

We are gracious and gallivanting looks. The sea is inside all of us and empty.

The world stops and stands still, spins again.

Do we head up or down into darkness? Or off the curve entirely?

With no reference point, with the image entirely focused on a section, the angle becomes even more apparent, necessitating the body to turn, to flatten itself sideways against oncoming traffic.

What are the yellow lines for?

In case darkness fully overtakes us and we have to navigate by the glint of glow-in-the-dark stripes? Or are they slip-resistant, buffers against storms that will shatter windows and leave puddles of dissonance everywhere?

The yellow jars against the grain. They both run in parallel but the wood laminate ages better. But it is laminate, after all; a signifier of trees that could have been climbed up or down but in the end are only chopped and milled into smaller things.

In their place comes these simulations.

The image like a memory made by the provenance of a filmic eye, with its slight dislocation of colour from digital fidelity, or the half-frame of failure.

Here is the familiar and the fallible, a contemplation upon what isn’t too different from outside the edge of the frame. A glimpse of the repository of a country whose bread and butter is reflected in the familiar patterns of public housing, a weave of affordable imprecations that binds its citizens by and within pragmatic necessity.

Witness, for example, the row of potted flowers, like patients waiting to see a neighbourhood TCM practitioner. And below, in the void deck, a man is sat waiting, glued to his phone like the rest of us, for light to change, for the frame to end.

A perfect day to watch the world remade, again and again. The sun is the heritage of those who churn the land and reduce hills into riveted blueprints for dense dreams. The sky is the only thing that cannot be excavated, though it loses its shape in other ways, in sorrows of torrential rain that cannot be named.

The foreman, watching from the barely-there comfort of the bus-stop, is all of us, not waiting for the one bus that will arrive at proscribed intervals, a danger-keep out sign his steady companion, along with the casual consistency of traffic cones.

Cones are far more ubiquitous than we realise. They are in construction, in sports, in fashion. We wear them as warning and as a ward. They keep our lives bordered, believable.

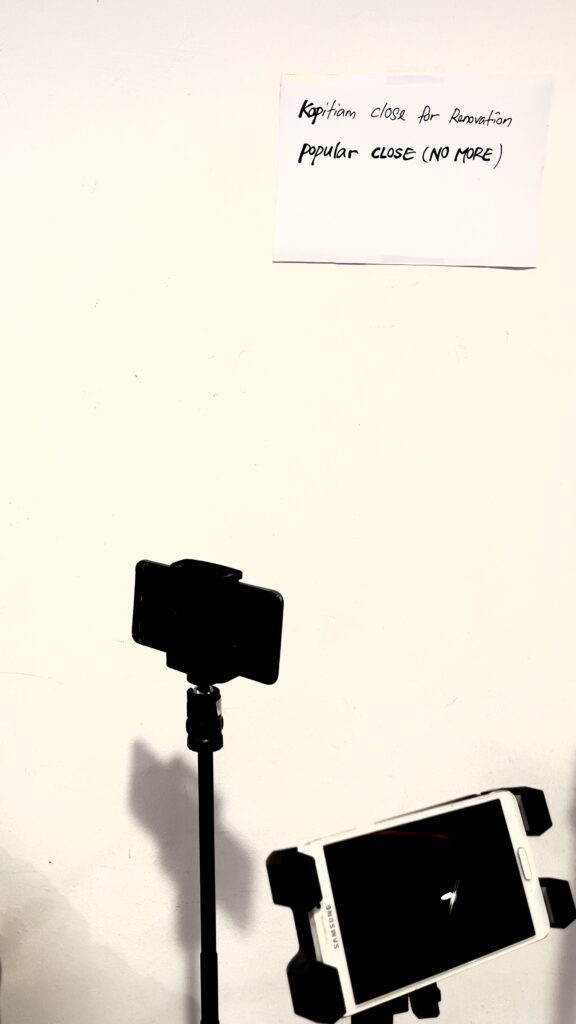

It is not the devices that are for sale, but their holders. It is not the pens and assessment books or the chicken rice stall that have sold out and shut, but the larger containers that hold them. No object is truly independent.

A tablet is intrinsically far more valuable than its spring loaded holder, and yet, here, it is nothing more than a prop, a mundane example of utility. But look closer. Not everything is tainted by the faceless pedigree of capitalism. The sign is handmade, seeks no audience or grammar, and is eminently cute in how it differentiates between the fates of the two establishments in question. Closure does not mean something is gone. It could be relocated. But in this case, ‘no more’ has a ring of finality about it.

Of course, mobile devices are also cameras, their invisible eye importuning passersby, a possible record of presence. And what is it exactly, about surveillance, that disturbs us so? Perhaps the idea of being seen without permission, of constituting the surface of the body for server rooms, mapped and marketed and yet as anonymous as the black screens that keep their secrets.

The body of a child is the representation of resistance. Pliable, indifferent to the norms of what is up or down, soft or loud. Standing up, running around, lying down, the child is a loaf of bread that will not cease its chatter, its uninhibited expression.

The mother, on the right of the frame, is made complicit in her relationship to the child by the angle of her unrelenting gaze and the slump of her shoulders. The latter is a universal gesture that holds equal measures of resignation and reprisal. Perhaps the latter has proven ineffectual. Perhaps the child understands that obstinance is only another word for performance.

Years later, this will be another story, enlarged through the focal length of memory, made bombastic and expansive. The child delivered a monologue on the floor. The child was given bread because customers were hesitant to enter. The mall security was called.

Today, it is a scene, one that reminds us of all the floors we did not dare to lie on when we were young, of all the rules that remained unbroken.

At Pantai Kampung Bahasa Kapor in Port Dickson, the tide pulls its blanket from eroded stone and mangrove roots, marshalled by an invisible moon in all its fullness. Just beyond swimming distance are two platforms for tankers to dock and receive gallons of refined oil. They mark the sea and the beach as pedestrians in their great game of fossil fuel dominance. They also wreck every single photo of the landscape. No amount of artistically framed trees in the foreground can overcome these utilitarian jetties of consumption.

My friends, who have been living for years in the town under the constant whine of an oil refinery, pillow rocks under the exposed roots of mangrove trees. They hope that roots will grow over and gird the rocks in the absence of sand, hoping they will not fall over in a gale. Maybe they will form a vanguard, rejuvenating this corner of the beach, allowing it to speak again.

These small acts of care are reminders of the beach as a place where we give and receive, the vastness of sand and the stateless body of water lapping up inside us.

Arms at leisure, arms in motion, arms with purpose, arms reaching into a small opening. Arms fishing, fishing, wishing.

The light sea green wall recalls fragments of seaweed parting before the prow of a speedboat dancing on the waves, unbroken, the town council slathering two coats every few years. The colour changes each time, but the politics remain the same.

The double-swung arms of the man like he is about to leap forward, past the frame of his retirement, into the ether of an unnamed composition.

And the cat is oblivious, or rather, we are oblivious to its musings; how it soaks up the serenades of passers-by, how slumber is a sideline for its true self.

I do not know why the bus stop was not dismantled.

It is a relic, a throwback to when SBS (our old, nationalised bus company) buses were also painted orange and white. These bus stops have largely been phased out, replaced by impersonal, functional structures that leave no impression, other than to offer their convenience in plexiglass and steel.

And yet, this one remains, walled in behind the hoardings of some undescribed new housing project. It is lifted at a rakish angle by a mound of earth, glaring at a row of condominium blocks that stake their claim as the city’s truer skyline.

This shelter is one where no bus will go, except the ones that run on alternate roads, a different world where the passengers look nothing like us and where the seats are all occupied in another spectrum.

Maybe this sighting of the bus stop is a tear in the flimsy in-between, where dereliction here is a bustle over there. Who knows how long it will be here, in this country where the past is often an impediment for progress, until it is commemorated with a slab of concrete and a suitable epitaph for a walking trail.

I think of the sea whenever I see tarpaulin. It is everywhere on boats, covering nets and styrofoam boxes of newly-caught fish. It is the first line of defence against the eroding truth of sea-spray. Somehow, this two-tone blue, maybe a proxy for the shades of an ocean, predominates the production of tarpaulin, or tarp, as we fondly call it, this fore-shortening a kind of affection, as if it could shelter us a little more.

Glimpsed out of its element in an office, it feels reduced somehow. Granted, it still protects a squad of false ceiling boards while the air-conditioning gets replaced, but it telegraphs an awkward smile, grateful for a shard of sunlight yet not quite close enough to taste the sea with its rough and tumble truth, its absence of politics.